Bondy and Bernie: Beer in the '80s

Eight years ago Matt Kirkegaard sought an interview with Alan Bond toget his recollections about the heady days of brewing in the 1980s. He wasn’t able to obtain the interview and, with the news today of Alan Bond’s death, now won’t get the chance. Here though is an article he wrote about those days that touches on Alan Bond’s influence on brewing the continues today…

REACHING the legal drinking age in the 80s, I was more concerned with the volume than the quality of beer available. There weren’t too many decisions to be made in my salad days of beer drinking. None of this mid-strength, imported, low-carb, nonsense. Jug or stubby was about it.

I was also none too concerned about the business of making it. All that mattered was that it was there, and being a born and bred Queenslander it had to be XXXX. Castlemaine Perkins, Castlemaine Tooheys, it was all XXXX to me.

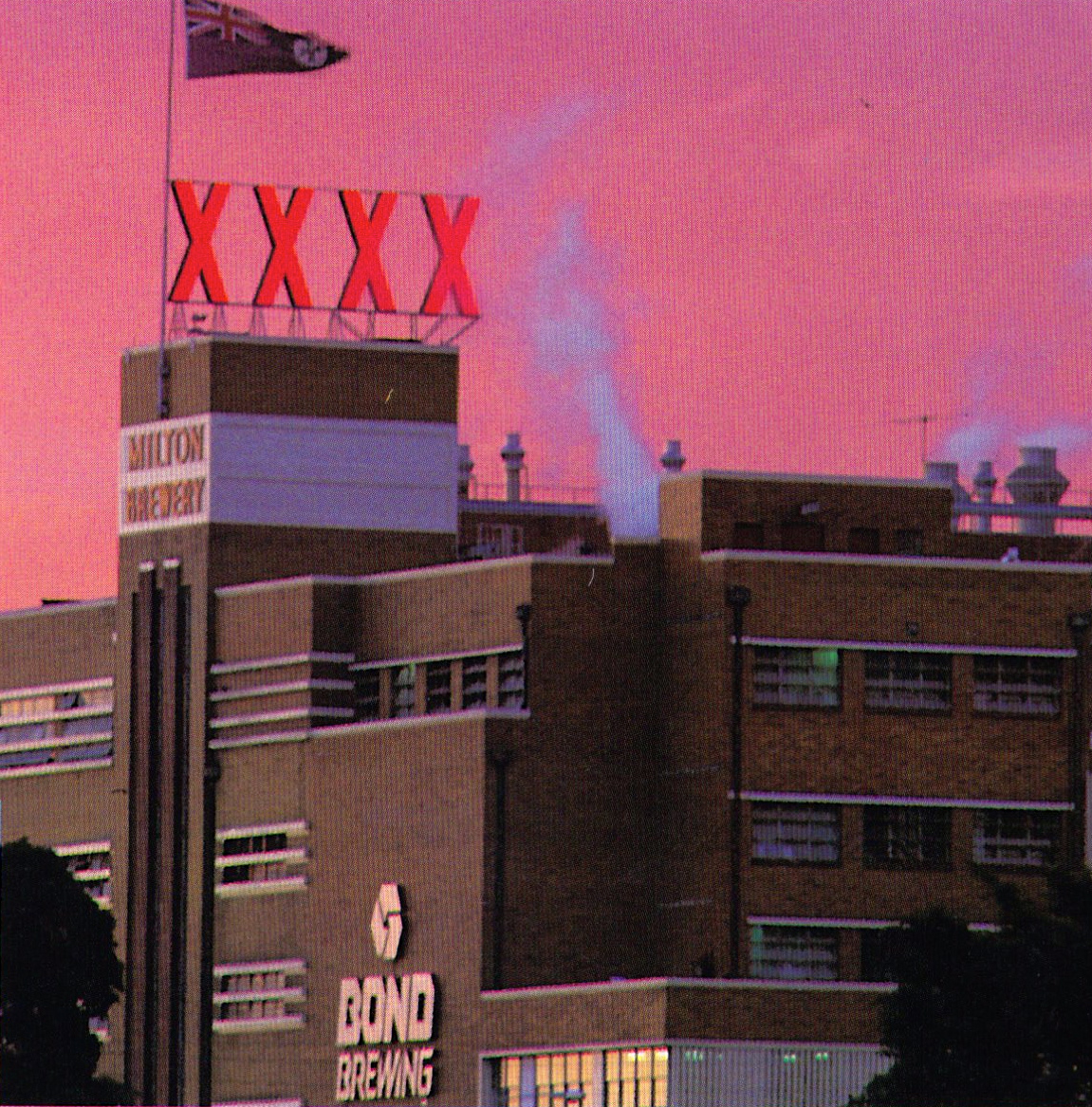

That is until a day in 1985 when everything changed. A new sign adorned the building where the famous Mr XXXX used to be. It said “Bond Brewing” and the address on the cans beside the image of the iconic Milton Brewery said, ‘Western Australia’.

Times they were a-changing and they had changed quickly.

Fourth generation brewer Bill Cooper had become the Managing Director of the family company in 1977. Bill recalls that at the start of the 80s there were 10 members of the industry group, Australian Associated Brewers.

“There were 10 members, but only nine companies,” Bill says. “The tenth member represented Queensland Breweries, the Bulimba Brewery, which was owned by Carlton.”

Hello Bond Brewing. (photo courtesy http://www.beerlines.me/)

The other brewers in the association were Carlton and United, Tooths, Tooheys, Castlemaine Perkins, Tasmanian Breweries–comprised of Boags and Cascade–Coopers, South Australian Brewing, Swan and Courage.

“Swan was the first to go,” Bill recalls.

There had been much speculation in the late ’70s about the possible purchase of many of the major breweries and Swan Brewing was not immune.

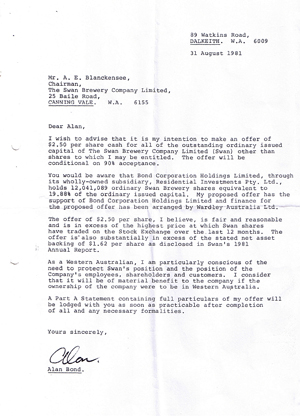

During 1980 Robert Holmes a Court bought up two million shares–three per cent of the company–and by December 1980 Alan Bond’s Residential Developments Pty Ltd also owned over 10 per cent of the company.

With concerns about takeovers rife, much talk in the industry was spent planning how to forestall outside takeovers. It seems the brewers figured that it was better to unite than fall to outsiders.

In the book Swan: History of a Brewery, author Suzanne Welborn recounts a meeting in Brisbane between Swan’s General Manager Lloyd Zampatti and Chairman Alan Blanckensee and their counterparts at Castlemaine to discuss a possible merger in the lead up to the period.

The talk came to nothing.

Welborn’s book also describes an alleged handshake deal that took place in a hotel carpark between Zampatti and Lloyd Hartigan from Toohey’s to the effect that they would look at merging if either brewery was threatened.

But in mid 1981, as Bond moved to take over the West Australian brewery, there was no one to prevent it. By then Tooheys was Castlemaine Tooheys as the potential saviours had made other arrangements and merged in March 1980.

Lion Nathan’s Bill Taylor was brewing at Castlemaine in Brisbane at the time and recalls the merger taking place with little fanfare.

“The company secretary arrived at the brewery one morning and announced that we had just merged with Tooheys and the company was changing its name to Castlemaine Tooheys,” Bill recalls.

There may have been little fanfare but Bill says that the mergers were an important part of the evolution of Australia’s brewing business.

“It was a merger between two significant brewing companies in Queensland and New South Wales,” Bill says.

“There was synergy there. Castlemaine was selling beer 2,000 kilometres north in Cairns but not 100 kilometres south in Tweed Heads.”

Taylor was still there in 1985 when Bond, having captured both Swan and the America’s Cup, set sail for Castlemaine Tooheys.

“Back then that was the biggest takeover in Australian corporate history,” Bill says now. “It was more than a billion dollars, and there had never been a billion dollar deal in Australian business at that time.”

“Bondy created a corporate identity called Bond Brewing, so the Castlemaine sign that was on the front of the brewery came down and a big silver logo went up that said ‘Bond Brewing’ and the head office was St Georges Terrace, Perth went on the label.”

At the time, the deal shook up the brewing world – or at least the world of beer drinkers. For Taylor it shows how ingrained our beers were in our psyche then.

“It’s interesting, people wouldn’t care about that sort of change if it was a pair of shoes, a camera or a washing machine or a refrigerator. If it was petrol no one would care,” he muses.

“But for some reason beer really has this emotional connection with people, or at least it did. I’m not sure if it does any more, but it did.”

Another young brewer at XXXX at the time was Ian Chant who had joined the brewery in 1978. Ian recalls a heady time when not only the bigger brewers were going through times of change, he says the ’80s also saw the rise of the microbrewer as well, and they were looking for people to do their brewing.

“I got invited to join a number of start-ups in the 80s but I guess I recognised that you can have a passion for brewing, but at the end of the day it’s a unit cost business,” he said.

“My gut told me that a lot of people were going to go out there and get small breweries, pub breweries, up and running and were not going to succeed.”

He declined the offers.

Still, he harboured some reservations about the new brewing monoliths that were forming, including his employer.

“At Castlemaine we had 80 per cent market share and Carlton and United Breweries had 16 or 17 per cent,” Chant recalls

“I had the feeling at the time that a lot of people in the company thought Castlemaine had an unassailable position, but my personal view was this wasn’t the case.

“I felt that there was a time for change and that time was not too far away.”

For Castlemaine Tooheys in Queensland, change came in the form of Bernie Power.

As Power describes it, he had several hotels in Queensland from far north in the Cape right down to the Gold Coast and he sold XXXX. He is matter of fact in describing the situation faced by hoteliers at the time.

“You basically did what you were told,” he says. “If you were a lessee of a hotel, you didn’t sell the opposition beer, there’s no question about that.

“In those days if you were with a tied house, that was all you sold. You only sold exactly what Castlemaine Perkins gave you.”

Conditions got even tougher just before Christmas 1985 when Castlemaine changed the terms of credit it extended to hoteliers from 30 days to seven, with CUB following suit a week later.

“It almost sent a large number of hoteliers to the wall. It was absolutely devastating, as you can imagine, at Christmas when you had your big buy in and were relying on 30 days credit.”

It was the last straw for Power who resolved to do something about it.

“I decided to look at building a small brewery,” Power says modestly.

Learning that Philippines Brewer San Miguel had a small brewing plant in storage on Guam that they weren’t going to go ahead with, he made inquiries of the company. It turned out that the plant had been badly stored and the equipment damaged and worthless.

Still, his investigations showed him two things. There was a lot of equipment out there and, more importantly, there was a market.

“It became quite clear to me that there was a lot of discontent in the marketplace. Hoteliers and others were angry, frustrated and didn’t like the company, or both companies in fact.”

“It was quite clear to me as a hotelier that there would be an opportunity to build a brewery.”

Still his research also showed him how little he knew about establishing a brewery, so he set out to learn.

He contacted Andrew Crook, former head brewer at XXXX and a man Power describes as the doyen of Australian brewers. Crook put him in contact with a dream team of international brewers and three young employees at Castlemaine.

Suddenly Ian Chant, the man who had been refusing an increasing number of offers to start breweries because of concerns about their viability, got an offer he couldn’t refuse.

“Most of these people had maybe a couple of million dollars at the absolute maximum, and they thought they could do it on a shoestring,” he said.

“When this one with Bernie came up, suddenly we had a situation where you had a hotelier who had a number of distribution outlets, but more to the point he had a plan to secure funds.”

The two others that Power approached, Malcolm Davies and Steve Guyt, shared Chant’s view that Castlemaine Tooheys was vulnerable.

“When Bernie had a talk to us we shared the vision and we had the same feeling about what was going to happen in the industry.

“And we decided that we were going to play a part in it.”

In one of the most successful brand launches in beer history, Power’s Lager burst upon the market quickly taking a 10 per cent share in its home market.

Ironically, the seeds of its downfall were sown in this success. Despite a period of intense competition lasting several years, Power ended up partnering with CUB before selling the brewery in 1992.

“The facts are that we ran out of beer, literally on the first day, and never caught up,” is how Power describes the situation.

“What we should have done was focussed on our state so we could supply it properly and manage it properly.”

Power’s assessment is backed up by another of the 80s’ brewing mavericks who drew swords against the might of the large breweries, Chuck Hahn.

“Bernie had really good brewers, he chose a good brewery site there in Yatala and very quickly took a big market share in Queensland,” Hahn says.

“If Bernie had been less ambitious he could have become the leading Queensland brewer, but he wanted to take on the nation.”

Hahn had himself set up a brewery, going to market with his Hahn Premium Lager in March 1988, six months after Power.

He too met with immediate success and a swag of awards. However, within months of opening, the 1988 budget came down and fundamentally changed the marketplace adding a 20 per cent sales tax onto the existing excise. Keating’s “recession we had to have” followed soon after, the combination seeing off many of the small brewers.

By decade’s end Bond was gone, with Swan and Castlemaine Tooheys bought out by Lion Nathan. The Hahn Brewery and SAB followed in the early 90s, while Power’s went to join CUB, now The Foster’s Group…but IXL, Elders, Elliot and Kunkel that’s another 2,000 words.

This era of beer and brewing cannot truly be captured in such a short space. The histories of beers are also the histories of people, and they are compelling stories. But what is the legacy of the period?

For Bill Taylor, the consumer has won.

“I think from the consumer’s point of view it’s opened up the country, there’s a wider variety of beers available to the consumer – all that occurred opened up the markets,” he says.

“We used to sell beer in Cairns, but we wouldn’t sell it past Tweed Heads. I don’t know why. Was it the fear of the parochial consumer, did we think that New South Welshmen wouldn’t drink a Fourex?

“All that’s sort of broken down now and the turning point seemed to be the 80s, so the consumer I think has been the big winner.”

Ian Chant sees the social changes that took place, but he also looks at the period with a pride common to all who worked on the Power’s Project.

“Maybe I’ve got tickets on the Power’s team, but in 1987 Castlemaine Perkins had over 82 per cent marketshare – they don’t command anywhere near that marketshare any longer and I think that Power’s was the vehicle that broke that dominance.”