CAMRA: The defenders of beer

If with water you fill up your glasses,

You’ll never write anything wise,

For ale is the horse of Parnassus

Which hurries a bard to the skies.

(Thomas Moore)

Once upon a time all beer was local. As a perishable product with a short shelf life, historically beer didn’t travel too far from its brewery. In the United Kingdom beer was traditionally ale, conditioned in the cask from which it was served.

In 1933 however, a brewing company called Watney introduced a new method of storing and dispensing beer to the UK market. By filtering, pasteurising, adding carbon dioxide and chilling the beer before sealing it in kegs, the beer lasted longer and was easier to dispense. It was great for brewers and pub landlords, but many felt that the character of English ales suffered for the convenience. Still, over thirty years this style grew to dominate. Traditional cask beer, neither filtered, pasteurised nor chilled continued to be brewed in the meantime, with breweries often producing both types of beer.

Easily portable kegs lent themselves perfectly to being sold nationally and large national breweries began to flourish, absorbing many of the small regional breweries in the process. The number of breweries halved between 1940 and 1960 and by the mid-1960s six conglomerates produced most of the beer and owned the majority of the pubs in Britain. Known as the ‘nationals’ these huge companies had the economic clout and logistical ability to market keg beer throughout Britain.

By the 1970s much British beer was about as appealing as Adelaide water; the strength was declining, and with it the concept of regional variety and distinctive tastes. But the 1970s were also the decade of mass movements and consumer protest. Enter a bunch of savvy young whippersnappers to kick up a hell of a fuss about the state of their beer.

In 1971 four young men from the north-west of England formed the Campaign for Real Ales – or CAMRA – to protect and preserve their favourite drink.

One of the founders, Michael Hardman, says they were just four men of 25 and under, who knew very little about traditional British beer except that some tasted wonderful and some tasted awful.

“We established the campaign rather jokingly with a wish that every pub should have at least one traditional draught beer available, and blow what else it sold, that’s none of our business,” he said.

“Out of the woodwork came hundreds of people who had been thinking along our lines for years and knew the answers to a lot of our questions.”

The organisation stuttered at first but then grew rapidly. CAMRA was active in recruiting members and campaigning via a central headquarters and regional branches. By its second AGM, in 1973, CAMRA boasted a membership of over 1,000 people. They adopted the term ‘real ale’ to describe “traditionally brewed and properly served draught beer.”

CAMRA aimed to fend off the standardisation of beer and the monopolisation of the market by large centralised brewing companies. They did this by celebrating, promoting and encouraging decentralisation, specialisation and regional diversity in the brewing industry. Their methods were ingenious, and sometimes downright cheeky.

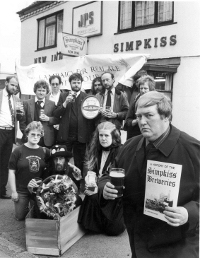

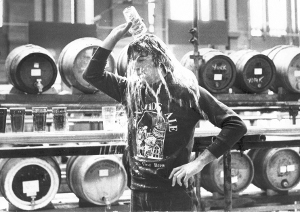

Terry Jones of Monty Python and founder of Penhros Brewery pouring his own brewery’s beer over his head to open the Great British Beer Festival.

In the spirit of the era there were lots of marches, such as the protest against the closure of Joules brewery (founded in the 12th century, but owned then by Bass Charrington, one of the big six conglomerates). Over 600 members turned out to drink, protest and attend a meeting held in the local cinema. The event was well covered by radio and the BBC’s prime-time Nationwide television program. It was a popular way for members from around the country to meet (and drink) whilst simultaneously spreading the real ale message to a wider audience, and frustrating the big six brewing companies.

Other approaches got right into the big breweries’ nerve centres. The monthly newsletter, What’s Brewing, organised CAMRA members to team up to buy shares in large brewing companies so they could vote against the closures of small breweries at shareholders’ meetings and ask tricky questions.

Chris Holmes was President of CAMRA in 1975 and has since gone on to run a chain of pubs in the East Midlands. Chris said that one of his favourite campaigns involved Mansfield brewery, an independent brewery but one that didn’t produce any real ale.

“We organised a survey in the streets of Mansfield. We asked Mansfield Bitter drinkers whether they thought the beer was better, worse or the same as it was two years ago when Mansfield Bitter was real ale,” Chris said. “The vast majority said it was worse.”

“We gave these results to the press and we got loads of coverage. Mansfield Brewery were livid. Livid!”

Chris later asked questions related to this exercise at the brewery’s AGM. Success was not immediate, but within two years Mansfield had begun to brew ‘real ale’ again.

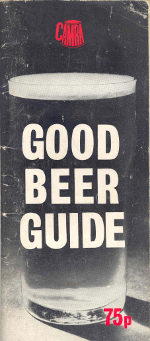

Literature was another important driver of the real ale movement. What’s Brewing arrived on the scene in June 1972 and CAMRA’s indispensable annual Good Beer Guide came out in 1974 with a county by county, pub by pub breakdown of where to find the best beer.

But other beer writers were also on the case independently of CAMRA.

To write 1973’s The Beer Drinker’s Companion author Frank Baillie must have had a wonderful time. He visited every brewery in the country to find out what the difference really was between keg beer and cask beer. His book provided a detailed explanation of brewing processes, methods of dispensing beer, appropriate temperatures for serving, the flavours and strength, and changes and trends in the brewing industry. He also presented a gazetteer of all the breweries in Britain, differentiating between “The Regional (Independent) Brewers” and “The National Brewers”.

The Companion was written and presented in an unpretentious style with little of the wine-snob prose we endure today. The entry for George Bateman & Sons Ltd shows how Baillie used simple language for his depictions. “Bitter. Malty-flavoured with above-average hopping rate.” Still, he held back from being too critical of the breweries and beers he didn’t like though for fear of legal action.

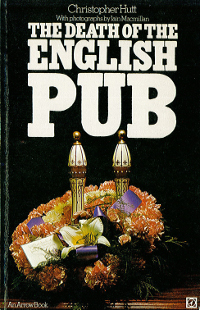

On the other hand Chris Hutt’s The Death of the English Pub, also published in 1973, reads more like a call to arms for the beer-drinking Briton. Hutt pushed, pulled and pleaded with beer drinkers using his skills of rhetoric to persuade them by interspersing the facts with his own opinionated narrative. His book was artfully presented with a symbolic front cover and moody black and white photography.

The Death openly sought to expose how the “objectives of the big brewers are to banish quality”, and the individual is overlooked in deference to company profits. The targets of his polemical arrows were clear and names were not withheld.

Hutt provided economic justification for his judgement that the alcoholic content of many beers had declined in recent years. He explained how some beers were weak enough to have been sold in the United States prohibition era. The gradual decline in strength was associated with the increasing profits of brewers. Hutt estimated the saving made in duty and raw materials between 1964 and 1970 at £11M. A price “paid by the beer drinker, because the brewers do not tell us when they weaken their products, and they do not lower their prices accordingly.”

A journalist by the name of Richard Boston cottoned on to the groundswell of discontented drinkers and wrote a regular column – Boston on Beer – that ran in the Saturday Guardian from 1973 to 1975. He says that it arose because he’d been abroad for some time.

“I came back and I was horrified by what they were doing to the pubs and friends said, ‘they’ve fucked up the beer as well, not just the architecture’.”

In 1976 Boston published a compilation of his column entitled Beer & Skittles. The book blended the characteristics of both Baillie and Hutt’s work, but came further from the left and developed its own quite different arguments. It overflows with references far and wide, including Hardy, Hogarth, Dickens, Sassoon, Orwell and Graham Greene and economists such as J K Galbraith and E F Schumacher.

Boston injected an added element of wit that had been lacking, intermingling fact and opinion with amusing anecdotes. He recounted the story of a German civil servant who shot 13 of his barbeque guests when they complained that the beer he had served was warm. On home brewing he said, “This will fill your house with a delicious aroma. If your spouse dislikes it, change your spouse.”

But, according to Michael Hardman, the most significant single contribution to the publicity of CAMRA was an article by a prestigious architectural writer. Ian Nairn’s journalism was noted for its criticism of public agencies’ design, planning and works and its effects on the urban environment of England, but he also commented on the architecture and interior design of English pubs.

In a 1974 article in the Weekly Review of the Sunday Times Nairn confessed his membership to CAMRA and summed up their concerns. He did not refer to design or architecture, but rather to breweries and beer, using wine as a frame of reference to help explain his argument.

“True draught bitter in Britain is in its way as good as the best of claret or hock – without the snobbery or the expense. And unlike good wine, it doesn’t exist anywhere else,” he wrote.

Nairn combined the arguments from The Companion and The Death, which he believed “dovetailed beautifully”, and he reinforced this with a discussion of his favourite brewers, their beers and the pubs he knew that served the beers he recommended. He saw two points as standing out.

“One is keg versus draught beer; the second is the arbitrary extinction of local flavours in favour of a ‘national brew’.”

Baillie wrote his book unaware of CAMRA. After it was published he read about the organisation in his local paper and joined up. In contrast, by the time The Death was published Hutt had become its second chairman.

Richard Boston maintained a surprising distance from the organisation. Before his death he told me that when he was writing his column he found CAMRA a “bit boring”, although his writing led some people to believe that he had founded CAMRA. Although his book made many points sympathetic to the organisation’s stance, he also criticised them for their inflexibility.

“It has been said that some of their members would drink castor oil if it came from a hand pump, and would reject nectar if it had no more than looked at carbon dioxide,” he wrote.

Regardless of any allegiance with the campaign, all of these writers did a great service to the British beer drinker and to the industry. Together CAMRA and the beer writers fuelled a remarkable consumer-led resistance to standardised beer. Ordinary small breweries with low status and restricted local markets have been reincarnated (sometimes literally) as specialist artisan breweries. This provided a superb example to beer drinkers the world over. People began to take beer – and beer drinkers – seriously and craft brewing and microbreweries followed on.

Despite their success, the brewing industry is a constant battle between the craft of the brewer and the realities imposed by business. CAMRA is a monument to how consumers banding together can ensure that the celebration of the craft is good business.