The rise of the “paddock to pint” philosophy July 2022

This series on Beer Tourism is proudly brought to you by Australia’s Craft Beer Capital.

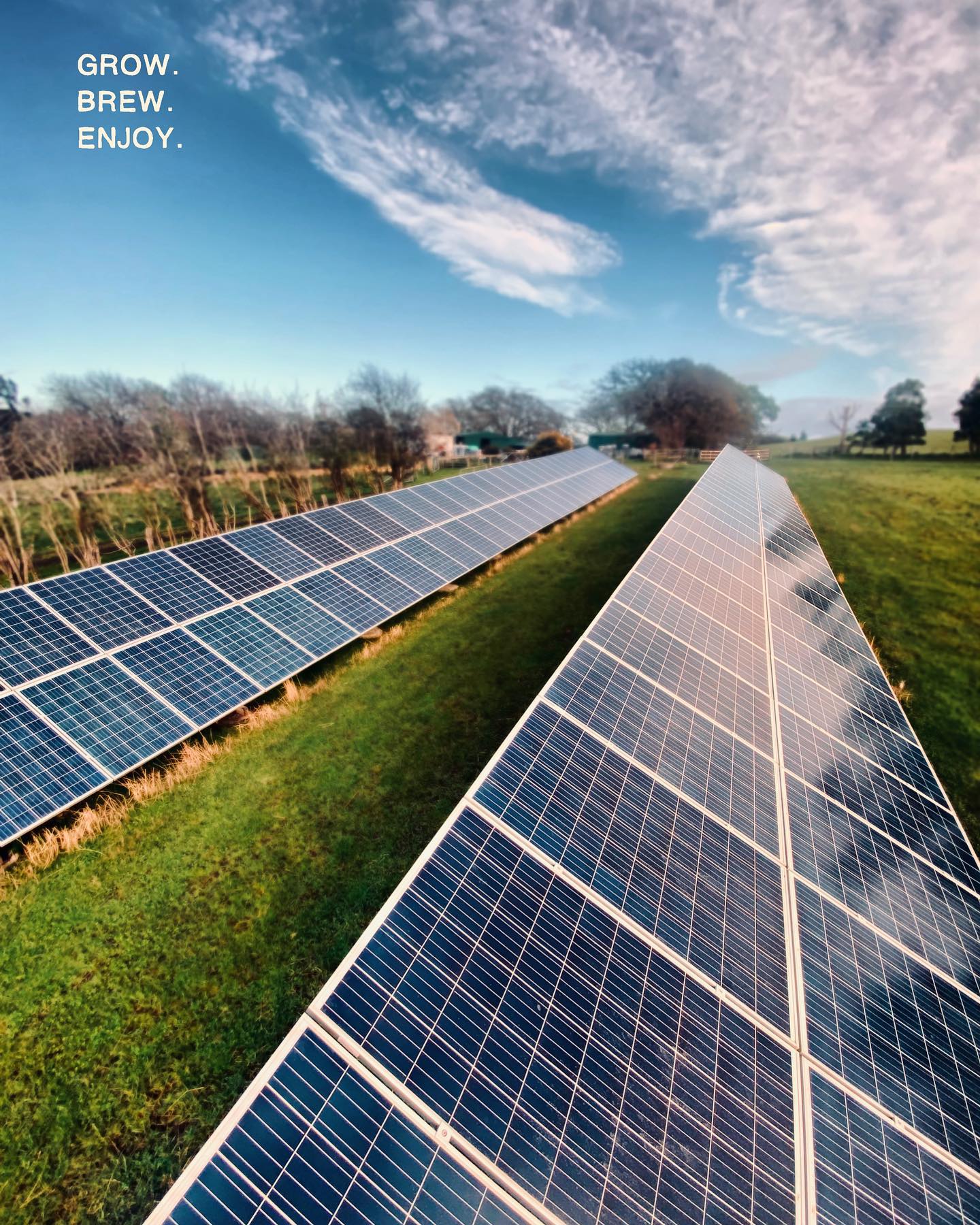

Van Dieman Brewing in Tasmania

A focus on local produce during COVID accelerated an ongoing consumer trend, but for beer, the “paddock to pint” concept of brewing with locally-sourced ingredients can be a major challenge.

Unlike single-origin beverages such as wine or spirits, the story of beer, its ingredients and how it was made, can be much more difficult to tell. It is also tied to the nebulous concept of “local” – does that encompass ingredients only grown in your backyard, or does it extend to Australia-wide produce?

Provenance is something to which customers are increasingly paying attention, and brewers are taking on the challenge across Australia.

Some breweries, such as Van Dieman Brewing in Tasmania, have been living the “paddock to pint” reality.

“Much like brewing, there are different levels in which you can look at this,” explained Van Dieman brewer and founder Will Tatchell.

“I know for us, it’s a really conscious effort to do what we’re doing and achieve what we’re doing. It’s very much been an organic growth of the brewery and farm working in unison.”

For the last five years, Van Dieman has been producing a line of beers entirely estate-originated.

“There’s nothing that comes in from off-farm or that goes off-farm to be processed,” Tatchell explained.

But while the majority of breweries are not so fortunate as to be located on a farm or in a growing region for one of the main ingredients, that has not stopped brewers looking to buy as locally as they can from Australian-owned suppliers.

Challenges of local ingredients

The “paddock to pint” concept can seem out of reach for brewers, particularly those in urban areas or in regions that are inhospitable for growing some of the main ingredients of beer.

Tatchell said he was extremely conscious of the fact that Van Dieman is in a privileged position, but that was exactly the reason why they felt it was their obligation to make the “paddock to pint” ideal a reality.

“I’m really conscious of the fact that what we’re doing is almost the ultimate goal as far as farm brewery or locality brewing,” he said.

“One of the reasons that I do it is because we have the capacity to do it… so there’s almost an obligation here for me to continue this and do it, as well as the fact that obviously I love it and enjoy it.”

That’s not to say that there aren’t challenges with adding even more processes to the beer production journey with growing raw ingredients and the impact this can have on brewing operations.

“We can try and recreate beers [but] there are always going to be those nuances and differences in ingredients on a yearly basis that we have to work with, we have to be smart about how there are challenges involved with doing that,” explained Tatchell.

Designating the boundaries of local can also be tricky. But Tatchell said that while Van Dieman takes its ingredients from as local as is probably possible, that definition shouldn’t be limiting for other breweries which don’t have the luxury of an on-site farm.

“Define local. It’s like trying to define what’s craft. Australia is still local. Supporting suppliers and growers, something like Hilltop Hops Farm in Brisbane or anything grown here from HPA, if we were to grab hops from them, we’re still using Australian-grown hops.”

Five Barrels Brewing’s Bière De Maison

Five Barrels Brewing is one of these breweries looking to focus further on local provenance for its beer, and as a result, brewed its all-Australian Bière De Maison for the GABS Festivals this year.

“I really wanted to take the production team out to some hop fields and out to Voyager to see the malting facilities and things like that, so that we could start to understand a little bit more about the ingredients that we’re using in our beers,” explained Five Barrels’ owner Phillip O’Shea.

“It was quite a nice, little organic, kind of process that really stemmed from us wanting to expand our knowledge and understanding of everything that went into beer.”

Five Barrels decided on an all-Aussie sourced beer using Voyager Malt, yeast from Mogwai Labs, and hops from Ryefield Hops.

“We framed it as a celebration of all the people that are involved in these things, because, you know, it was one of the things that we didn’t really understand… and use GABS as a platform to highlight the amazing work that some of these people do.

“It was really quite an eye-opening experience and something we wanted to tell people that hundreds and hundreds of hands are involved in making that schooner a reality.”

But a lot of suppliers are small, and might not be able to supply great swathes of the brewing industry which can limit their reach.

“[Just] like we can’t supply every pub in Wollongong, they can’t supply every brewery in Australia,” O’Shea reasoned.

“Voyager Malt, his grain isn’t homogenised, it’s not blended with a whole bunch of different farmers, so they can’t scale beyond that size because farmers only produce so much grain.”

Chad McGregor afrom Eclipse Brewing Co. which is planning on investing in local ingredients agreed and said that while local ingredients companies were investing in growth, they might not be able to keep up with demand in the short and medium term.

“Both the craft malting and hop production industries are in their infancy in WA, and demand is currently outstripping supply, but it’s great to see that expansions are underway across the local supply chain,” he explained.

“The reality of this is that we need to balance our local content in our beers so we can grow with these companies.

“While we can’t source 100 per cent of our ingredients locally, we have setup Eclipse to be able to support the local supply chain as their capabilities grow.”

Consumers and “paddock to pint”

Brewing with local ingredients can be considered a major focus for the brewers themselves, as they challenge themselves to perfect their art and innovate.

But increasingly it is becoming a focus for consumers as well, who are beginning to look at locality and provenance in many purchasing decisions.

“People are becoming conscious of where their fruit and vegetables and meat come from,” said Tatchell.

“And they make a conscious effort to try and get stuff from as close as possible to where their home is.”

Using local ingredients can also anchor a producer in their locality, developing those community links but also providing a holistic taste of the area to visitors.

However, unlike the wine industry or even with food products like coffee and beef, the provenance of the ingredients in beer is a bit more of a complex issue to relay to consumers.

“People understand wine, whiskey, cider, even spirits because they’re almost exclusively of a singular origin… it’s very easy for people to wrap their heads around that.

“As much as we don’t want to overcomplicate it, it’s four key ingredients, hops, water, malt, and yeast. A lot of people have a grasp on hops nowadays, and the variety of flavours and aromas that can come out of that.

“Malt is starting to be understood, but water, people probably couldn’t really care less what water is in a beer and yeast is probably something that’s again [not as well understood].

“And we go talking about all four of them at once, I think it’s a little bit lost. And it’s a challenge. It’s a challenge to try and provide as much information as we can without overloading the consumer that is just there to enjoy their beer.”

Customer education then becomes a key element of telling the story of a beer.

“[As a generalisation] people aren’t necessarily demanding that level of information about their beer. So it’s still an education piece in trying to get people to inherently understand that beer is an agricultural product in liquid form.

“And as brewers, we manipulate those products, much like a chef does, to craft something that, at the end of the day, that’s enjoyable for as many people as possible. I’m just not sure whether people are there yet – ready to think about their beer as much as what as us brewers would like.

“I regularly put on my consumer hat and ask ‘what am I after out of this? Is it hitting a mark as for a particular beer, is it hitting the mark of is it enjoyable? Is it fun? Is it exciting? Is it drinkable? Is it balanced? Is it drinkable?’”

Why do it?

While there are undeniable challenges with using local ingredients, even new breweries such as Eclipse Brewing Co. realise its importance.

“WA is a world-class food producer [but] a lot of unimproved produce is exported prior to value adding.

“Supporting the value-adding process to our local produce at a local level through malting at Mortlock, and further adding value through the brewing process, means more money stays in the local communities where we intend to operate, providing more opportunities for innovation and growth in regional areas,” explained Chad McGregor.

“We’ve been stoked with the malt and hop flavour profiles that we have produced from local ingredients, and the feedback from the punters has been great!

“It’s [also] a great story! Aussies are all about having a crack, and our local suppliers are the embodiment of this ethos. They are all entering uncharted territory for the sake of better local beers, and hopefully our support helps give them the confidence to continue.”

There were also environmental benefits, McGregor said.

“Reducing our food miles is a major step towards reducing our carbon footprint and minimising our environmental impact.”

For brewers, it’s also a chance to innovate and experiment further, taking on the challenges of locally-sourced ingredients.

“I’m stubborn. I love a challenge and curiosity will always get the better of me,” explained Will Tachell.

[Having grown up on a farm] we can always see that there was this disconnect between and this is probably speaking probably 10 years ago, there was a bit of disconnect between where ingredients came from and what that equated to in a beer.

“When I was a kid we used to grow malting barley for Boags and Cascade.

“Once we started brewing on the farm it was always a lofty goal to produce stuff on the farm and never take it off farm to produce a beverage.

“Yes absolutely it’s easier to pick up the phone to a brilliant supplier that we have these days in the industry and get something arguably a better quality at a fraction of the speed that it takes to produce it.”

But the results of being able to source ingredients internationally could prove to be a potential disadvantage in the long run, Tachell suggested.

“I see that as arguably one of the weak points in the brewing industry, that it has become very much a monoculture.

“So you can create a recipe and we have access to ingredients from all around the world so we can produce a German-style lager here with German malt, German yeast, dial up a water profile that is of German water quality… and hopefully, you can’t taste the difference between something produced historically in Germany and produced in Australia.”

But it also means that brewers have greater control over what they put in their beer – whether they grow it themselves or can visit the local farm on which the ingredients are being grown.

“I love that because it keeps me fresh, we’re constantly challenged and I’m constantly testing my limits, what we can do, how we challenge ourselves, how we learn,” Tatchell explained.

“So it’s an ongoing process. And it’s an ongoing learning curve, which I think you hear of anyone that is in this business. The moment you stop learning, you might as well tap out because you’ve potentially reached where you can plateau.”