Exploring the chestnut beers of France

I have always been a bit of a conservative when it comes to beer and beer ingredients, preferring the simple barley-malt, water, hops and yeast approach to brewing. Some of the things that in recent years I have found added to beverages called ‘beer’ immediately reinforce my allegiance to this stance, but others, I am quick to admit, roundly challenge it. Some however, just leave me scratching my head. Chestnuts are certainly one of the latter.

After moving to France to live two years ago, my first encounter with chestnuts was to find them being roasted on mobile braziers at every second street corner, the chilly winter air scented with their warm and alluring aroma. In the eating however, I found them bland and disappointing, wondering what all the fuss was about, and pining for some warm roasted macadamias.

Vendor of hot roasted chestnuts, Aix-en-Provence, December

My subsequent discovery of many French beers that incorporate chestnuts in one form or another started me on a protracted and ongoing mission to learn about the history of chestnuts and chestnut beers, and to try to answer the question ‘why use them in the making of beer?’ Here is some of what I have discovered.

The use of the sweet chestnut (Castanea sativa) as a food source has a very long history in Europe. It has rightly been called the ‘most humanised’ of all European forest trees. Ancient Greek literature contains references to the preparation of the nuts by boiling and roasting. Early in the Christian era, the Romans used the tree mainly as a source of timber, but to some extent also as a food source, and encouraged its systematic cultivation and use wherever it grew naturally within the expanding empire. The widespread use in Europe of chestnuts in coppices and in orchards for staple food production however, probably began in the early Middle Ages, after the decline of the Roman Empire.

Chestnut civilisations

The white-fleshed chestnut became a staple source of carbohydrate during the Middle Ages, substituting for cereals where these would not grow well, such as in barren mountainous country. The planting and cultivation of the species flourished, and in some parts of Europe chestnuts became so indispensable for human survival that the cultures dependent on them have been labelled ‘chestnut civilisations’. During this chestnut ‘golden age’, a wide range of cultivated varieties developed, with different ripening periods, types of use, and ranges of distribution.

Interest in the chestnut as a food declined greatly in Europe during the past couple of centuries, partly as a result of their replacement by imported crops, such as maize and potatoes. Chestnuts came to be regarded as ‘peasant food’, as ‘the bread of the poor’, and were shunned by the affluent.

The decline in chestnut production for food is indicated by the following figures (in thousands of tonnes) just for the period from 1965 to 1995, for four main European producing nations: France, 82 down to 11; Italy, 87 to 52; Portugal, 47 to 19; and Spain, 88 to 10.

The chestnut forests in Europe still cover some 2.5 million hectares, but most of that area is now dedicated to timber production. Only about one-fifth is now used for fruit production. France and Italy together account for about 80 per cent of the total chestnut forest area in Europe, with Spain, Portugal and Switzerland together contributing a further 10 per cent.

Developing chestnut fruit, Ardeche, August

Contrary to the long-term decline, in the past few decades there has been a renewal of interest in the European chestnut forests. Old abandoned orchards, seen as having aesthetic, ecological and cultural heritage values, have been revitalised. Increasing demand for natural, environmentally-friendly and traditional products has led not only to the revitalisation of old orchards, but to the planting of new orchards with high quality varieties.

During the centuries when chestnuts were a staple food, countless creative ways were developed of preparing them for consumption. For example, they could be roasted, or boiled in water or milk and could be consumed as a vegetable, or as a substitute for bread, or used for their inherent sweetness in sweets and desserts.

Chestnut revival

A fresh, raw chestnut typically contains about 50 per cent water, 25 per cent starch, 10 per cent sucrose, and small amounts of fibre, protein, fat and minerals. Significantly, chestnuts have a very much lower fat content than most other nuts. They’re also gluten free!

The nutritional qualities of chestnuts, together with the modern demand for wholesome foods and for the restoration of traditional products and values, has lately given them renewed standing, and freed them from the centuries old stigma of poverty. In addition to the revival of traditional chestnut-based products, new goods and services are being developed. Among the many new products is chestnut beer.

The commercial production of beer using a proportion of chestnut in one form or another as an adjunct to malted barley is not an uncommon occurrence at present in Europe’s traditional chestnut-growing countries, especially in Italy and France. The idea seems to have started in the 1990s in Corsica, and a more appropriate place cannot be imagined from an historical point of view.

Corsica, the more northerly of the two large islands that sit beside Italy and below France in the western Mediterranean Sea, has been part of France since 1768. It was briefly independent for a decade or so prior to then, but for most of the time from the 1200s until the French takeover it was ruled by the republic of Genoa. Considering the mobile grazing practices of the Corsicans to be uncivilised, in the 1500s Genoa imposed a policy of chestnut planting and cultivation on the mountainous island’s population.

This resulted eventually in the transformation of the ‘backward’ shepherds into chestnut farmers, and to their more permanent settlement in villages. Corsica’s chestnut culture developed fully in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, providing flour for human consumption, fodder for animals (sheep, goats and pigs), and surplus fresh fruits for trade, thus supporting a booming human population. As in other parts of Europe, the chestnut culture collapsed by the end of the nineteenth century, aided by the development of local industries and the consequent flow of rural population to urban centres. The trend was encouraged by the island’s new French rulers, who thought chestnut farming to be backward, and favoured the cultivation of grain.

Corsica’s chestnut beer

It the 1980s, history began to be reversed with the development of initiatives to rehabilitate Corsica’s decaying chestnut trees, and to establish a new chestnut economy. One aspect of the island’s contemporary chestnut economy is the chestnut-based beer, Pietra, the creation of Corsican couple, Dominique and Armelle Sialelli. Pietra was first produced in north-eastern mainland France, around 1994, but since 1996 has been brewed in a new purpose-built facility near Bastia, Corsica’s pre-eminent port and main commercial town. The Pietra brewery was the first to be built in Corsica, and the Pietra beer the first anywhere, as far as I know, to be made with chestnut flour as a raw material.

Closely following the introduction of Pietra, Christian Bourganel of southern France’s Ardeche district, the country’s main chestnut-producing ‘department’, developed a chestnut-influenced beer, which he called Combel. It was introduced in 1997, having been brewed for him at the Brasserie Castelain in northern France. Bourganel opened his own brewery in 2000 at Vals les Bains, in Ardeche, and rebranded Combel as Bourganel Biere aux marrons de l’Ardeche.

Marron, by the way, is the term in French for a particular sort of chestnut, of superior quality and culinary usefulness. It is derived from the Italian marrone, meaning the same thing, and gave rise to maroon, the brownish-crimson colour in English. Curiously, it seems also to be related to marronnier, the French word for the horse-chestnut tree (Aesculus hippocastanum), the fruit of which is ironically inedible. More generally, the edible fruit of the sweet chestnut is known in French as chataigne, derived from the Latin castanea. Similarly, the tree is the chataignier, and a place planted with chestnut trees is a chataigneraie.

Fresh chestnuts at fruit markets, Aix-en-Provence, October

Reverting to beer, Pietra is by far the most easily procurable chestnut-influenced variety in France today. It and the Bourganel product have been joined by many others, of various styles, and employing chestnut in various forms and quantities as an adjunct in the mash. Most are the small-batch products of tiny breweries, so are hard to find. I’ve only been able to purchase seven so far, including Pietra and Bourganel, although there may be more than a dozen currently in production around France. Not to mention the number of beers produced elsewhere in southern Europe, especially in Italy.

Australia’s chestnut beer

I must add that some other French beers are made with a small proportion (less than 2 per cent), of the distinctively-flavoured chestnut honey (miel de chataignier), but that is another story entirely. It is perhaps indicative of Pietra’s dominance in the category that it was the inspiration for Australia’s first chestnut beer, produced by Ben Kraus of Bridge Road Brewers at Beechworth in north-eastern Victoria, and launched in 2008. The Beechworth area is one of several places in the world beyond its natural range where Castanea sativa has been planted in commercial quantities in recent decades. Ben’s chestnut beer project was encouraged and assisted by local chestnut growers.

French chestnut beer

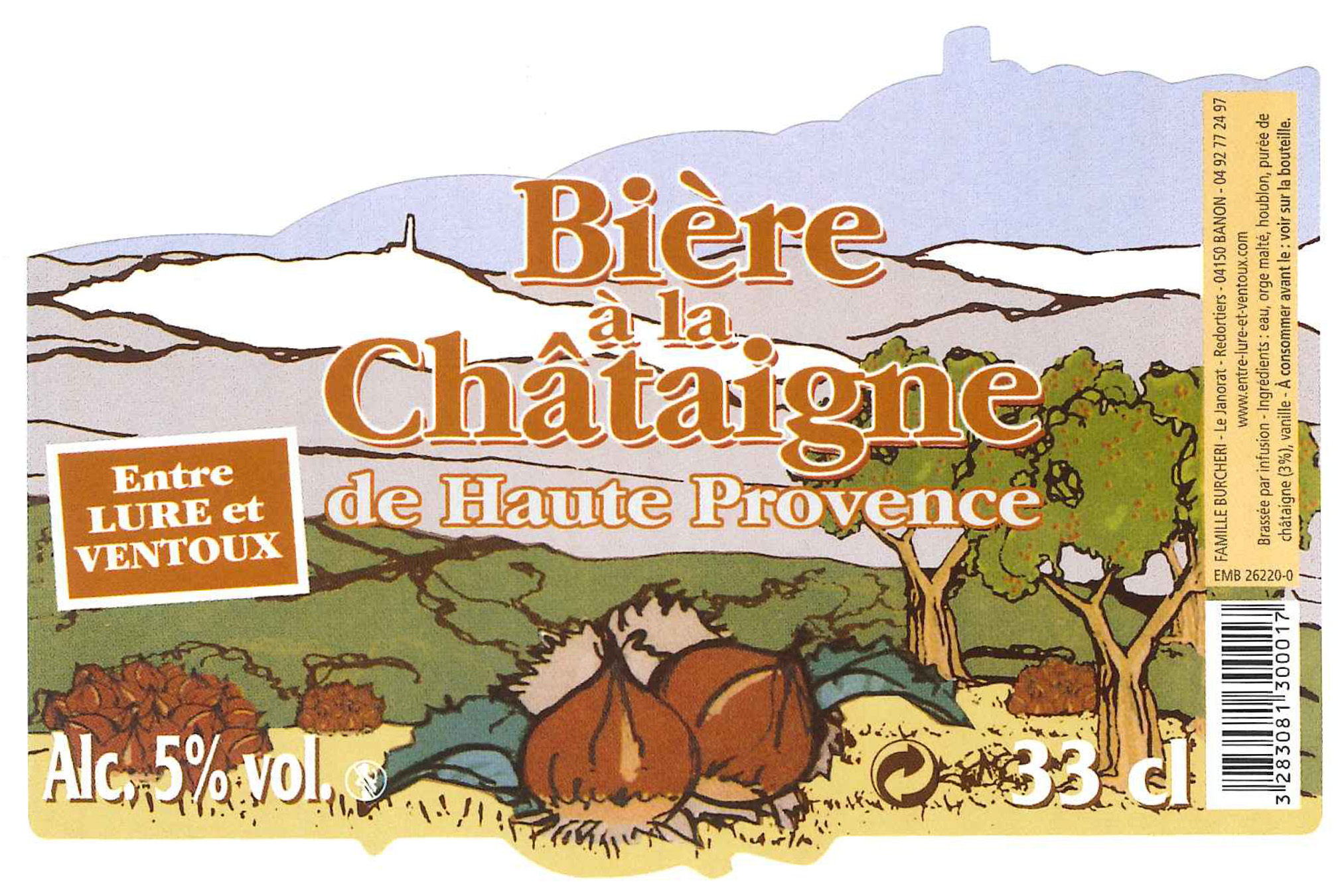

Some French brewers of chestnut beers disclose the amount of chestnut used in their recipes, and some, for instance Pietra, do not. Bourganel states that 2.5 per cent ‘brisures’ (chips) of chestnut is used in its Biere aux marrons. Similarly, Biere a la Chataigne de Haute Provence (marketed by the Burcheri family) uses 3 per cent of chestnut puree. Both beers also contain a quantity of vanilla, which is detectable in the flavour, and perhaps disguises any effect of the tiny amount of chestnut.

Two much more earnest and perhaps sincere efforts at incorporating chestnut into beer have been made at Brasserie de la Croix du Rat (founded in 2000) at St Cyprien, in the south-west, and Brasserie Artisanale de Beaucaire (founded in 2009), at Beaucaire, an ancient town on the western bank of the Rhone. At the former place, brewer Stephen Dunne uses 18 per cent chestnut and 82 per cent barley malt in his Biere a la Chataigne. At the latter, brewer Johanna Petit uses ‘greater than 20 per cent’ of chestnut in her Biere aux chataignes de la montagne noire. Johanna also makes a stout with a lesser proportion of roasted chestnuts.

Chestnut beer label

Which brings me to the all-important questions of ‘why put chestnut in beer?’ and ‘what difference does it make?’

In order to attempt to answer these questions, I recently assembled an expert tasting panel, several different chestnut beers, and a jar of chestnut spread, the latter to provide a possible clue as to what flavours we were trying to detect in the beers. For comparison with Stephen Dunne’s Biere a la Chataigne, I also obtained some bottles of his Biere Blonde, which the brewer told me was very similar except for the chestnuts.

Before embarking upon the practical component of this investigation, recourse was had to the many consumer evaluations of chestnut beer, particularly of Pietra, to be found posted on the global beer forums RateBeer and Beer Advocate. Far from clarifying the matter, this experience compounded my confusion.

Ingredients in La Croix du Rat

Conclusive testing

A very small proportion of reviewers, perhaps those with superior olfactory and gustatory senses, reported being able to detect the influence of the chestnut, with one saying ‘the chestnutty flavour is nicely present in the aroma; it is also interestingly and discreetly hidden somewhere in the background.’

Another adding, ‘now I know this beer was brewed with chestnuts and you can certainly pick that up in the nose’.

The vast majority, however, were defeated. Here’s what they had to say about it:

Pietra boasts that it has the taste of chestnuts, ‘but I’d have to be hard pressed to guess this solely from tasting it’.

‘I wasn’t able to find tonnes of chestnuts in aroma and flavour.’

‘Searching chestnut in flavour was vain effort.’

‘Nuts? Where? In the beer? I don’t think so.’

Another record of defeat can be found in the following hilarious commentary: ‘I sniffed it up and down till I was dizzy looking for the nuttiness, but other than the power of suggestion, I can’t say I found much. I offered a sample to my dog Snorky, who has a nose of incredible acuity and encyclopaedic memory of variegated olfactory nuances. “Chestnut, boy, chestnut! go get ’em!” I prompted, and put the snifter down for him to analyse. He took a single sniff and looked like I’d offered him a curd of low-cal tofu. So there you have it: no chestnut, and not much interest.’

Determined to do better with my own assemblage of samples, the hands-on part of the investigation was commenced. We tasted and re-tasted Bourganel’s Biere aux marrons de l’Ardeche, but failed to discern any chestnut flavours or aromas, concluding that they were masked by the presence in this beer of a small but noticeable amount of vanilla. We tasted and re-tasted Biere a la Chataigne de Haute Provence from Famille Burcheri, but again failed to detect any chestnut flavours or aromas, although the vanilla in this product was thankfully more difficult to recognise. On a separate occasion, we compared Stephen Dunne’s Biere a la Chataigne, heavily dosed with 18 per cent chestnuts, with his otherwise similar Biere Blonde, both of which are made ‘sans vanille’. There were indeed slight differences in flavour, but, disappointingly, we were unable to describe them, or attribute them to the presence or absence of chestnuts.

Our conclusion must therefore be that the taste and aroma effects of using chestnut in the making of beer are at most very subtle, even with as much as a 20 per cent contribution. It could be said, however, that there is a slight textural effect—a smoother, softer mouth-feel, and a finer, creamier foam—and perhaps some additional bitterness, from that inherent quality of the inner skin of the chestnut, some of which can be left behind after they are peeled.

Our conclusion must therefore be that the taste and aroma effects of using chestnut in the making of beer are at most very subtle, even with as much as a 20 per cent contribution. It could be said, however, that there is a slight textural effect—a smoother, softer mouth-feel, and a finer, creamier foam—and perhaps some additional bitterness, from that inherent quality of the inner skin of the chestnut, some of which can be left behind after they are peeled.

Cultural purpose

So, why drink chestnut beers? Having discovered through experimentation that the use of chestnuts makes little difference to the product, and bearing in mind my stated preference for the simple barley-malt, water, hops and yeast approach to making beer, I might conclude that there is little point. There is a point however, to contributing to the restoration and revitalisation of this ancient and fascinating element of European food culture, by supporting the development of new uses for it; helping to conserve cultural heritage by brewing beer. I’ll drink to that.